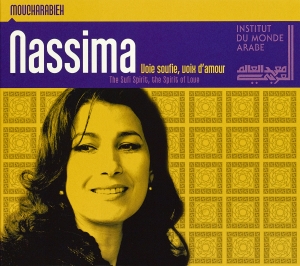

Nassima

Acknowledged for her virtuosity in the interpretation of the Arab-Andalucian repertoire, Nassima has gathered here the most beautiful works of the great Sufi masters, from Ibn cArabî to the emir Adb el-Kader. To original, moving music, she revisits almost a century of tasawwuf mysticism, dwelling on its quest for universal peace.

“My music is the crossroads of life I have gathered in its heart Songs of love and peace A message from eternity Which I want to make mine”

Tracklist

1 – My Much beloved God – 5’46

2 – Layla! – 5’38

3 – A Vision of the Beloved – 6’02

4 – Lute solo – 1’36

5 – I am Love – 4’18

6 – Divine Presence – 4’21

7 – O my Lord – 0’56

8 – Abraham’s Sacrifice – 5’04

9 – Divine Love – 4’38

10 – In the Heart of the Night – 5’35

11 – Wisdom, followed by Laments – 6’01

12 – Peace… Salâm – 3’05

Interpreters and instruments

Nassima (singing, oud, mandole)

Pierre Rigopoulos (daff, zarb, derbouka, choir)

Noureddine Aliane (oud, choir)

Rachid Brahim Djelloul (violin, choir)

Mustapha Kaïd (choir)

About

The texts set to music and sung by Nassima come under the inner mystical or spiritual dimension of Islam commonly known as Sufism (tasawwuf in Arabic). « The living heart of Islam », Sufism has explored and boldly expressed some fundamental, often-overlooked teachings of the Koran: the primacy of the relationship of love between God and Man, God being revealed to the faithful through proximity and intimacy; the universalism of Divine mercy along with the acknowledgement of other religions; and God as peace and completeness. Having permeated Islamic culture for centuries, Sufism now enjoys a renewal of interest in many “Moslem countries” where diverse ideologies have failed and where it often serves as an antidote to fundamentalism. Furthermore, Sufism now attracts many westerners in search of authentic spiritual nourishment. Its characteristic openness of mind already plays a providential role in today’s globalisation, which must not be only mercantile for fear of driving humanity to suicide.

In Sufism, one reaches God through two complementary ways, in truth identical as to their bases: love and knowledge, forever intertwined in the spiritual experience. The masters whose poems are featured here are both great lovers of God and great Gnostics. Indeed, their love is not made of sentimentalism; it transcends the physical world because it is precisely of a metaphysical nature. This is evidenced in the poems by Ibn cArabî and by his disciple —centuries later— the emir Abd el-Kader: the cosmic love that drives them breaks all narrow dogmatism, all religious ostracism. They celebrate the Divine Presence throughout the world, and all forms of adoration with none debarred. Their spiritual experience is so strong that it lifts the veil between God and mankind (“I am at the same time love, the lover and the beloved”, says the emir). It breaks barriers between the various denominations (“My heart can accommodate all shapes” writes Ibn cArabî). This universalism, so plenary, so open, again originates in the Koran. Let us not confuse this with syncretism: whoever finds fulfilment within his own spiritual tradition has access to other traditions.

The poetic expression shares with mysticism a common, ineffable essence as well as a common recourse to symbols and to the original ambiguity of language. Prose cannot account for inner experiences while poetry allows one to suggest spiritual truths that one cannot or will not formally explain. To bear witness to this experience both powerful and subtle, the Sufis resort to such realities of this world as wine and love, which they transmute on the spiritual and mystical level. They therefore use a terminology seemingly secular; yet it is but a setting to express in human language what pertains to the upper worlds. “Layla”, for example, often refers to the Divine Essence in Sufi literature. Moslem jurists, obviously, focused on the literal meaning, which could not fail to shock them. “So delightful was the night which united us, both embraced in the same tunic, cheek against cheek” writes Ibn al-Fârid. The same cry of ecstasy is to be found in the Andalucian poem that suggests only at the end that the embrace of these lovers does not pertain to this world. “[…] We then rose without worrying about shaking our clothes, on which there was no stain.” For it is true that mystical poets sometimes sustained ambiguity, as though they wanted to flout censors. The ceaseless toing and froing between levels of meaning fuels a tension that is never resolved.

Mystical poets, just like their secular counterparts, are meant to be sung or at least chanted. Indeed, for the spiritual being, the music he hears here below is like an echo of celestial music and the Divine Word. According to certain traditions, angels managed to lock up Adam’s soul in a body after they charmed it with music. The approach of the initiate then consists in going up the path of Manifestation by liberating his soul through music. Through its cosmic origin, music is a preferred means of spiritual awakening. The samâc, or “spiritual listening”, is one of the methods used by men to try and reach ecstasy. For the enlightened one, all sounds, whether natural or artificial, evoke God, for in reality they invoke Him. “The seven heavens and the earth and all beings therein declare His glory. There is not a thing but celebrates His praise and yet you understand not how they declare His glory.” (Koran. XVII, 44.) The Sufi is therefore not only a visionary for whom rise the veils of the tangible world. He also perceives earthly sounds as so many remembrances of the spiritual world.

Collective samâc sessions were widely practiced in medieval Islam. Participants would gather in mosques, zâwîyas etc. The singers or reciters declaimed their poems, often accompanying themselves with musical instruments. When emotion overflowed and ecstasy invaded the heart, the body too was set in motion: people clapped their hands and stomped their feet, shouted and started to “dance”, threw off their turbans, hurled their coats at the reciter or tore ithem apart. One could faint from ecstasy; sometimes, according to certain sources, even die from it. Let us not be mistake: besides the Sufis, such sessions comprised ulama, mufti and jurists who sometimes gave in to dancing. It even happened that jurists allowed samâc sessions and Sufi masters forbade them to their disciples. These “sober” masters would not listen to the human word, preferring the silence of the Absolute, which was eloquent to them. But saints no less great have made the samâc their spiritual vehicle.

As a conclusion, let us bring to mind that “Islam” comes from “salâm” —meaning Peace— which is one of the Divine names, one of His attributes, that mankind must appropriate. Peace, as related by Sheikh Bentounès, is not some artificial achievement acquired on the field of war. It is an inner state, deeply rooted in one’s being thanks to Gnosis, Knowledge and Love. Any other approach to Peace in today’s post-modern, headlong-rushing world, is doomed to failure. Henceforth, Peace is synonymous with universal conscience and spiritual humanism.

Éric Geoffroy

An interview with Nassima

You have gained international fame for your interpretation of the Arab-Andalusian repertoire. Why have you turned to a new musical and religious approach with the Sufi philosophy?

Ever since I was a little girl, I have sung Arab-Andalusian songs of love. This music is much inspired by Sufism. I used to sing, unknowingly, lyrics that had a Sufi dimension to them. For me, it was love, love between two people. I realise that I have always sung the joy of union and the grief of separation, but in the Sufi philosophy, love means divine love, intoxication is spiritual exhilaration and not earthly drunkenness. In Blida, my native town, I already sung texts by Sheikh Ahmed el-cAlawî, the great spiritual master of the Sufi brotherhoodAl-Alawiyya, yet I did not know these were Sufi texts. For me there was no difference between Sufi and sacred songs, it was the same. I did this naturally with my masters Dahmane Ben Achour, El Hadj Medjbeur and Sadek Bedjaoui, of the Arab-Andalusian school. It was only recently that I came to realise that I had been immersed in a Sufi environment.

You have lived in an especially tolerant environment: first at a young age and later on when you became a woman, you were able to attend music classes and you were protected by your masters — and this for our greatest pleasure…

Like other towns in the Maghreb, in the 15th century Blida hosted Andalucian people who had fled Spain after the fall of Granada, in successive waves. In my native town, all denominations were represented, as they had been at an earlier time in Andalusia, which has become the mythical land where once, long ago, the three religions —Moslem, Christian and Jewish— co-existed in perfect harmony. I was lucky to have great masters pass on this Arab-Andalusian heritage to me. This musical and poetic legacy is represented in the nuba, a classical suite that evolves crescendo and lasts approximately one hour. Its themes are courtly love, nature and nostalgia of the Andalucian land. The poems are sung is classical (muwashshah) or semi-classical (zadjal) language. It is the music from the time of the refugees: people sing a lot about Granada, Malaga, Cordoba. There are also such folk derivations of the nuba as the hawzî, characteristic of the Tlemcen region, the carûbî and shacbî in Algiers and the mahdjouz in Constantine. Furthermore, there is a repertoire of sacred songs like the madîh, which are praises to the prophet.

This album features Arab-Andalusian Sufi poets, both classical and contemporary, ranging from Ibn cArabî to Sheikh Khaled Bentounès. How did you chose their texts?

I wanted to give pride of place to the Andalucian and Maghreb mystics, to spread them amongst the general public, although I also admire the Sufi poets of the Machrek. Their texts have deeply moved me. I discovered the emir Abd el-Kader and chose to interpret his beautiful poem “I am Love”. The emir was always inspired by the great Sufi Ibn cArabî, who was his spiritual master even though they did not live in the same period. I wanted to make the link between master and disciple. It is a beautiful text, whose Arab rhyme is superb. It is very close to that of Ibn cArabî, one of the greatest poets ever in all languages.

This also moves your Algerian soul. One can feel that to sing emir Abd el-Kader’s poem means a lot to you.

I wanted to reveal him to a large number of people. He was more than just a resistance fighter and a great strategist. It was his mother, an erudite woman, who first taught him the Koran and the bases of theology. The emir was a Sufi mystic, an intellectual, a highly cultured man and a splendid poet.

Has your research given you another vision of Islam? Has it had an impact and consequences on your life?

I have found again the inner peace I lost when I left my native Algeria like many intellectuals, artists and families who had to expatriate. I wanted to talk about it, but it took a little time for it to ripen. Via Sufism, I got closer to Islam, which is a religion of peace —salâm, love and brotherhood. Furthermore, mystic poetry is the extension of the love songs I have been singing since I was a child. To love, know and respect one another: I find all this in these poems. Now, I am in total harmony with myself, at peace.

Isn’t this quest of Sufism a means to deliver yourself from the constraints confining you in Arab-Andalusian music?

As far as music was concerned, I was free to create what I wanted; it had to be made to measure. So I drew my inspiration from the modes. I reworked very old melodies with my own arrangements. Others are new. I sought the modes that move me more, that go with the lyrics about love from my childhood, about the Divine presence. The track Abraham’s Sacrifice was a delicate piece of work because Abraham is the father of all believers. I had to sum up the text. The audience will judge.

What is the message of this album?

Nowadays, I feel especially affected by the demonizing of Islam. Ibn cArabî said: “In me you can find everything, the three monotheist religions”, as well as: “Love is my religion and my faith.” The message of Sufism, which is the heart of Islam, spreads very strong universal values, such as living together as brothers. The emir Abd el-Kader stated: “There is room for everyone.” When I was reading the “The International Book of Peace” where such eminent figures from the world over as Nelson Mandela, Sheikh Khaled Bentounès, the Dalaï-lama and Abbé Pierre deliver a message of universal peace, it aroused the need to make this album. Being Algerian, wanting to launch an appeal for peace, love and mutual respect, I was inspired to offer audiences an album dealing with the same themes, drawn from Sufi poetry.

How did you prepare this album?

This is the outcome of three years of research during which I consulted books, attended conferences, questioned Sufi friends, visited exhibitions, surfed the web etc. We worked a lot with the musicians. The only instruments on this album are a cûd, a violin and percussion: a daf and a zarb, which are really close to Sufism and whose sound really befits the song and choruses.

How would you qualify the music accompanying these Sufi songs?

I have drawn my inspiration from Andalucian modes. The music for Abd el-Kader’s text is in C Major, it is a mawwâl. As a tribute to him, I wanted to render its “Algerianity” with a modern Algerian folk melody. For each text, I have journeyed through the zidân (hidjâz), raml el mâya and mezmoum modes, all perfectly suited for mystic poetry. I also worked on the sihlî, which sounds more contemporary. It is music that leads us with a ballad to discover splendid works by poets who chose the way of love, the only way to peace.

Today, do you think you could sing this repertoire in your native country?

I hope so. In 2003, I went back to Algeria and sang in Algiers’ largest venue, Ibn Khaldoun. The national radio and television were there, delighted that I was back on an Algerian stage. I had been away for ten years! I had the great pleasure to renew with my public and my country. I sang with such emotion, my throat was knotted at first. There were ululations coming from all sides. Specialists told me: “Your voice has truly evolved, your departure was constructive.”

You have settled in Paris. Isn’t this a way to put up with being away, to find words to express exile and uprooting?

Whenever I’m on a stage, I feel at home. Wherever I travel in the world, I feel I am both at home and in the country where I am invited. The stage is the only place where I feel at ease, in my traditional dress, with my instrument, surrounded by my companions, singing in my native tongue. I recreate my universe as I sing, exchanging and dialoguing with others.

Intrerview by Caroline Bourgine, journalist

Short biographies of the Arab-Andalusian Sufi masters

Abû Madyân al-Ghawth (1126-1198)

Nicknamed « shaykh al-Mashâyikh » (the master of masters) by Ibn cArabî, who nursed a great admiration for him and quoted him in his work more than he did any other master, Abû Madyân was born into a humble family in Cantillana, near Sevilla. Attracted by famous masters of the Almeria school for their asceticism, he was also influenced by the imam el-Ghazâlî and by one of his Moroccan masters, Ibn Hirzihim (« sidi Harazem »). But his spiritual instructor was Abû Yacza, in Morocco, a Berber known as « Yalannour » (the owner of light). When he came back from the Orient, al-Ghawth settled in Béjaïa where he enjoyed unprecedented influence in the Maghreb while he was still alive. Nevertheless, the master only left a small number of spiritual writings. The sovereign Yacqûb el-Mansour, the Almohade, no doubt worried about such success, called him back to his capital, Marrakech. But as he arrived near Tlemcen, Abû Madyân al-Ghawth fell ill and died. He now rests in El-Oubbad, in accordance with his wishes. Highly venerated and regularly visited, he is now the Tlemcen’s patron saint.

Ibn cArabî (1165-1240)

Born in Murcia, Andalusia, Muhyî al-Dîn Abû cAbd Allâh Muhammad ibn cAlî ibn Muhammad al-Hâtimî, a famous Sufi philosopher, theologist, poet and mystic, is considered as the greatest master of Moslem spirituality (al-Shaykh al-Akbar). For over thirty years, he journeyed throughout the Moslem world from Andalusia to Anatolia, tirelessly teaching his disciples, before he settled in Damascus. He was the author of a monumental production comprising over four hundred works, in which he approached all aspects of spiritual life. His doctrine based on the uniqueness of reality or “existential monism” dominated and revived Sufi spirituality, at times arousing strong resistance in the midst of Islam. The Andalucian master was the bearer of a universal message summed up by this statement: “Love is my religion and my faith.” He died in 1240 and his body rests in Damascus proper, where Sultan Selim the First had a mausoleum built in his memory.

Mohamed Ibn Messaïb (died in 1768)

Abû Abdellah Mohamed Ibn Messaïb was born in Tlemcen in the early 18th century. He was the descendant of an Andalucian family that had first settled in Fès. A highly-valued singer, he practised the trade of weaver. A prolific poet, he was to write over 3034 pieces, of which only a minute part has reached us. His pilgrimage to Mecca inspired a poetic text about his route from Tlemcen to Mecca. He died in 1768 and his body rests in the cemetery Sidi Mohamed Essenoussi near Tlemcen, not far from that of Sidi Abû Madyân.

Emir Abd el-Kader (1807-1883)

The emir was born in Algeria, near Mascara. Better known as a great war leader as well as for his courage, his sense of organisation and the fierce resistance he opposed to the French colonial army than for the great mystic he was, highly cultured and immersed in a religious environment since his early childhood. His mother taught him the basic grounding of the Koran. He had always been attracted to Sufism, which he had plenty of time to study in-depth during his imprisonment in France, and later during his exile in Damascus where he lived until his death in 1883. His many writings reveal a man of heart, of great depth, full of respect for the human. He had a great love for justice, and during his stay in Syria he interceded on behalf of the Christians threatened by the Druze, saving them from certain death. According to his wishes, he was buried near his master Ibn cArabî in Damascus. On the 6th of July 1966, his ashes were transferred to the martyr cemetery El cAlia, in Algiers.

Sheikh Ahmed el-cAlawî (1874-1934)

Ahmed ibn Mustafa ibn cAlîwa, Abû el cAbbas el cAlawî, known as Ahmed el-cAlawî, was born in Mostaganem, Algeria. He was an interpreter of the Koran and a scholar of the Maliki law school. A mystic poet, he refounded the Shadhilite tarîqa, and then created the cAlawî-Darqâwî order, remaining its spiritual leader until his death in 1934, in Mostaganem. His teaching was built on submission to the sacred law and pure faith (El Imân), according to the teachings of the Prophet and the perfection of faith (El Ihsân) in the light of the knowledge of Allah, which Sufism allows one to attain. His poetic diwân was published several times, the latest in 1987. The examination of his book reveals that the mystic poet developed two themes: praise of the Divine beauty and praise of the Prophet’s beauty. His poetry is characterised by its simplicity. For him, the goal was to pass on his teachings to the largest possible number.

Sheikh Khaled Bentounès (born in 1949)

A native of Mostaganem, Algeria, Sheikh Khaled Bentounès was chosen as spiritual master by the assembly of wise men from the cAlawiyya brotherhood after his father died in 1975. “To my immense surprise” he says. A writer and conference speaker, he has federated all the brotherhood’s zâwiyas in the Maghreb, the Middle-East, Europe and Africa, and he has been spreading the traditional teachings of Sufism to thousands of adepts during his worldwide peregrinations. He has been defending a culture of peace and brotherhood, and his actions have been threefold: to spread authentic information on the reality of Islam so that it can be re-integrated into modernity; to establish a dialogue between religions; and to devote time and energy to humanitarian actions. He specifies that “while Islam is a body, Sufism is its heart, where one learns again to taste the flavour of God in the silence of the moment”.

Biographies collected by Nassima and professor Hadjadji

The recordings

1- My Much Beloved God – 5’46

Written by: Ibn cArabî

There is no being in the whole universe, who, saying my God,

Thinks not of the Highest. Indeed, myself, I say it

I know no lover who can feel a passion for another than Me,

For his passion is that he is my Lover

My Lover can only be the one who feels the same Love as mine

2- Layla ! – 5’38

Written by: Ahmed el-cAlawî

In love with Layla’s beauty, I became a slave

Stricken by a crazy love my heart wandered with her

O Layla “Peace be on you” I said and

“On all the noble successors”

O my God, grant a sublime blessing

To the torch of night, Taha the benefactor

3- A Vision of the Beloved – 6’02

Written by: Ahmed el-cAlawî

When my beloved one appeared, she was unveiled

O lover of the beloved, now is the time to contemplate her

Whoever wants to pierce our secret, let him come near and learn

All the knowledge will be displayed to him

O lover of the beloved, now is the time to contemplate her

4- Lute solo – 1’36

Traditional instrumental music

5- I am Love – 4’18

Written by: Emir Abd el-Kader

I am at the same time Love, the Lover and the Beloved

I am the Love secretly loved in broad daylight.

I say « I! » but is it possible that there is another than I?

I cease not to be within “Myself”, distraught and at loss

In “Me” are the expectations of humanity

The one who wants to read the Koran or understand its light

The one who wants to have a Torah or a Gospel

Or the one who wants a flute, psalms and a clear discourse

The one who wants a Mosque where he can pray to his Lord with fervour,

Or the one who wants a synagogue, or a church steeple and a crucifix,

The one who wants the Kaaba to embrace its stone,

Or who wants fetishes and idols

The one who wants a place to retreat to in isolation

Or the one who wants a tavern to praise beautiful women in

There lies in “Me” what was and what is

In us, in truth, rest both sign and evidence.

6- Divine Presence – 4’21

Written by: Ahmed el-cAlawî

These men who have slipped away to God!

Have melted like snow, I swear by God!

Are they baffled at divine contemplation?

You see them intoxicated, I swear by God!

Are they subjugated to the divine recall?

If the singer exalts divine beauty

They rise, transported by the grace of God

May God grant them His mercy, be satisfied with them

And flood his light breeze onto them

7- O my Lord – 0’56

Written by: Abû Madyân al-Ghawth

O You the Illustrious who sees what there is in the invisible world,

What there is underneath the earth when night has fallen.

You are the guide for those at total loss.

We have turned to You with firm hopes.

Everybody, impatient or imploring, addresses a prayer to You.

Should You forgive, to You the merit, to You the nobleness,

Should you show authority, You are the fair-minded judge.

8- Abraham’s Sacrifice – 5’04

Excerpts from an old poem

Abraham (Ibrahim in Arabic), the Patriarch, the Messenger, the Prophet and the friend of God, is the common father to all believers of the three monotheistic religions. In a dream he received an order to sacrifice his son to God as the absolute act of trust and obedience. On the third day, Ibrahim El Khalil (the Intimate) took his son, dressed in his best garments, to Mount Moriah where the sacrifice was to take place. Just as he was about to perform it, Archangel Gabriel placed a ram instead of his beloved son. Since then, Abraham’s sacrifice has been commemorated during the pilgrimage to the Mina valley.

9- Divine Love- 4’38

Written by: Ibn cArabî

Henceforth my heart accommodates all shapes

It is a pasture for gazelles, a monastery for monks

A home for idols, a Kaaba to the pilgrims,

The tables of the Torah, a copy of the Koran

My religion is Love, wherever its steeds take it to

Love is my religion and my faith.

10- In the Heart of the Night – 5’35

Andalusian poem

The Lover of my heart came to see me at dawn; I stood up

To pay him homage until he sat down.

O, my hope, I said, O source of all my aspirations!

So you have visited me, at night, unafraid of the guards?

Yes I was afraid, he answered, but passionate love has taken my soul and breath.

So we embraced and slept for a while

And our souls were almost stolen from us.

We then rose without worrying

About shaking our clothes on which there was no stain.

11- Wisdom, followed by Laments – 6’01

Traditional music arranged by Nassima

Wisdom – written by: Ibn cArabî

Had I been amongst the wise men, I would have exhausted my youth

Ceaselessly repeating God’s blessing and salvation for the Prophet,

In Hebrew and in Arabic, clapping my hands and beating the tambourine

As well as playing the rabâb, the source of infinite tenderness.

Laments – written by: Ibn Messaïb

Petitions addressed by the author to the Prophet so that he intercedes on his behalf during the Last Judgement day.

Followed by a madîh – by Ibn Messaïb

A traditional praise song to the Prophet.

12- Peace… Salâm – 3’05

Poem by Sheikh Khaled Bentounès recited by Nassima

In the name of God, the Lenient, the Merciful

Peace

It is the flower of intoxicating fragrance in the garden of tranquillity

It is the movement of love overwhelming, uniting hearts in forgiveness and indulgence

It is the mount of the hero fighting intolerance

It is the supreme meditation of the wise man immersed in the eternal presence

It is the quill of the scholar who arouses and passes on knowledge

It is the ink of the heavenly alphabet, the mystery of essence,

It is the foundation of the house of justice and dignity

It is the force saving men from monstrousness

It is the remedy of the heart for the anxiety of troubled souls

It is the hymn of cherubim carrying the divine throne.

It is the blessed name of God invoked by all the creation.

It is, at last, Salâm, to which I invite and devote all my devoutness

Apart from the poem by Khaled Bentounès, all other texts were first translated from Arabic into French by professor Hadjadji

- Reference : 321.078

- Ean : 794 881 795 529

- Main artist : Nassima (نسيمة)

- Year of recording : 2004

- Year of publishing : 2005

- Music style : Sufi Music

- Country : Algeria

- City of recording : Paris

- Main language : Arabic

- Composers : Nassima ; Traditional

- Lyricists : Ahmed el-‘Alawî ; Cheikh Khaled Bentounès ; Traditional

- Copyright : Institut du Monde Arabe