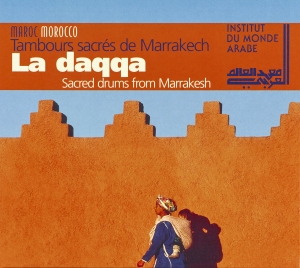

La Daqqa

The daqqa or “beating of drums” is a form of collective polyrhythmic music performed by men on percussion instruments, accompanied by choral chants. It takes place traditionally in Marrakesh and the surrounding area once a year, to mark the Ashura festivities held on the 10th day of the month of muharram, the first month of the year in the lunar calendar. This feastday is designed to remind the faithful of one of their duties that in fact constitutes one of the five pillars of Islam, that is, to pay the zakat, or legally obligatory alms, to the most underprivileged of the community. But other traditions and customs have become associated with this ritual obligation, e.g. visiting cemeteries, giving out sweetmeats and other activities that lend a carnival air to the whole event – music, transvestite disguises, ritual bonfires, sprinkling the passers-by with water…

Tracklist

1 – Recitative/Aït – 62’31

Interpreters and instruments

El Hadj Abdeslam

Abderrazzak Ben Moqadem

Mohamed Agair

Ahmed Aïtchall

Abderrahmane Atakkaout

Boubker Chhoud

Abderrahman Danja

El Hadi Driouich

Brahim Houdali

Mohamed Khirani

Jilali Laghnam

Mohamed Mardat

Mohamed Rachid Mouahid

Mustapha Msalhi

Moulay El Mahi Samrakandi

About

The daqqa or “beating of drums” is a form of collective polyrhythmic music performed by men on percussion instruments, accompanied by choral chants. It takes place traditionally in Marrakesh and the surrounding area once a year, to mark the Ashura festivities held on the 10th day of the month of muharram, the first month of the year in the lunar calendar. This feastday is designed to remind the faithful of one of their duties that in fact constitutes one of the five pillars of Islam, that is, to pay the zakat, or legally obligatory alms, to the most underprivileged of the community. But other traditions and customs have become associated with this ritual obligation, e.g. visiting cemeteries, giving out sweetmeats and other activities that lend a carnival air to the whole event – music, transvestite disguises, ritual bonfires, sprinkling the passers-by with water…

For children in Marrakesh, it is the festival of the ta’rija, a small, horn-shaped earthenware drum given them as a present by their parents. It’s a present that often has to be replaced – and more than once in some cases – for the fragile skin is easily pierced, thereby rendering the drum useless. These drums are specially made for this occasion and come from all over Morocco; the individual styles of certain pottery areas or towns can easily be recognised by the different forms. Thus a specific trade exists for this feast, involving a great number of people, rather like the business that has built up in France around the lily of the valley for May 1st.

Several weeks before the main Ashura feastday, one can hear drumming and singing in the houses of the medina and the small streets leading into it; the noise goes on day and night. But the townspeople are not just practising for amusement, they are aiming at the major and very solemn daqqa session to be held on the evening of the Ashura, which will take place at several different points in the town, each of which is the emblem for a whole group of quarters.

The young people practise over several weeks, going in for percussion competitions, always in the hope of being admitted into the great ceremony. The very small children, the most impatient, are the first to start, then gradually the older people join in. Little by little a sort of spontaneous election takes place. Street by street, the best drummers get together to form teams, which then join up to form leagues for each quarter; these inevitably get bigger and bigger as the great day draws near.

On the evening of the great daqqa session, they all go to the appointed place in their particular part of the town, but this time they are placed under the authority of the older, more experienced drummers, led by a person honoured with the title of al-amin (the guardian or judge), the master of ceremonies. He stands in the middle of a large circle formed around him by all the seated participants. Only then, under his implacable authority, does the daqqa begin. In the beginning, a slow, tense, solemn pace is maintained for a long while, gradually quickening up to the final apotheosis. Whilst the young people accompany themselves on their ta’rija, the adults do so with frame drums, clappers and the neffar (large horns or trumpets that blow a single note). The latter are only introduced in the last and final stage of the ceremony.

In reality, behind this whole act lies a secret test, the stakes of which are an inherent part of the structure of the daqqa ritual. The percussion part of this musical form consists of several strata of criss-crossed drummings, performed by a certain number of players, who are therefore clearly interdependent but who must at all costs form a single body by coordinating their movements and their playing. Moreover, there is no fixed rule about the beat for the daqqa – it is either double or triple, which means that there is a constant and irresistible impetus to accelerate the rhythm. So aside from any pleasure it may give, the hidden stakes brought into play in the organisation and structure of the daqqa are the lesson of self-control imparted to the novices, as they undergo the test of resistance to the general excitation of the rhythm. And this is why during the public performance and especially during the initial slow phases which can be prolonged deliberately over an infinitely long period, all the young players are kept under scrupulous observation. If one of them shows the slightest slip or slackening of the pace or even the tiniest quickening outside the general group rhythm, al-amin or one of his assistants rushes up to the poor defaulter, sweeps his drum to the ground without any delicacy of gesture and breaks it. No-one ever protests; this is the rule of the game.

Over and above the concrete aspect of this trial, another important point here is to remind the young people that the slowness of adults and old people should not only be considered as the sign of a loss of vitality, but also as something with its own specific advantage, i.e. increased control over the instincts and therefore over oneself.

The best players from this popular and traditional festivity have come together to form professional troupes who have made this music known to audiences all over the world.

Hassan Jouad – ethnomusicologist

A musical emblem

The daqqa is described as the musical emblem of Marrakesh. This is so true that certain people well-known for their piety, whom one could hardly imagine as lovers of this particular art, do in fact join discreetly in the groups of players, thanks to the anonymity provided by the cloak of darkness. Their presence brings comfort and inspiration to the novices inclined to sudden bursts of enthusiasm, whereas the basic essential of this art is an initiation into the virtue of patience.

Sitting in a circle and trying to exercise self-control recalls the conditions in which men assemble for the dhikr. Moreover, the recitative (aït) consisting of divine praises and prayers for the Prophet, in memory of the Sufi masters buried in Marrakesh, and the recollections of friendly outings to the large gardens situated around the medina, with all the reminders of Paradise that their inviting freshness contains, is largely borrowed from the spiritual exercises of the zaouia. This traditional art has not been severed from its spiritual origins, thus providing to all those who partake in it the possibility of achieving some inner or spiritual goal.

Traditional music creates a world of sound that exists outside time, and it is in this spirit that the art of the daqqa has evolved; following the same general rule, the slow movement of the percussion instruments at the beginning of the ceremony does not reveal or hint at anything of the final flaring blaze that will take place at dawn.The recitative as it is proclaimed in the middle of the night of the Ashura mingles with the percussive beats of the ta’rija-s; and in exactly the same way as the drumming, the economy of words is subject to the change of tempo.

In former times the great virtuosi of this art preferred to go far enough away from the circle of players so as to be able to judge the almost geometric quality of the performance. It has been said that Rabelais constructed his writings as if they were Gothic buildings; similarly, the rhythmic structure of the daqqa brings the form of the pyramid mysteriously to mind. The Egyptian writer Gamal Ghitany, well-known for his writings, including his fine meditations on the theme of “The Interior of the Pyramids” once attended a ceremony in Marrakesh, and was struck by this ressemblance in form.

Nowadays those who continue to practise the art of the daqqa also practise some very old games and sports, traditionally at the foot of the Koutoubia. According to tradition, their way of life is closely linked to the chivalrous ideals of the futuwwa – in what remains of the traditional world of the craftsmen’s guilds some reminiscences of this still survive. And whilst they wait for the occasional festivities to be held in their city or outside their locality, most of these artists carry on their work as craftsmen or rival each other and show off their sporting prowess in the big gardens around Marrakesh: hunting the sloughi or looking for rare birds…

The line of great masters

Together with certain story tellers from the Jemaa el-Fna square, with an oustandingly original style and force of narration, the symbol of the traditional popular arts of Marrakesh was the undisputed master Ben Moqadem, known as Baba. The townspeople held this man with his solemn gestures in real affection. When he presided the playing and the finale drew close, the audience would watch his famous white turban, which the movements of his head would inevitably finish by unwinding. It was never certain whether Baba deliberately made his headwear come undone in this way or whether the cloth, affected from within by the final flare-up of the playing, quite simply came unwound by itself.

Today his nephew and disciple Abderrazzak Ben Moqadem carries on the family tradition, resisting as far he can the growing tendency to consider this art as folklore. He in turn has taken the name of Baba and works closely with the two masters El-Hadj Abdeslam and Bâ Jaddi, both of unquestionable authority, the living embodiment in modern-day Marrakesh of the art of the daqqa.

They hold complementary roles during the Ashura festivities, but both are concerned with leading the ceremony to its rightful conclusion from the moment it starts in the middle of the night to the final blaze of drumming after the dawn prayer.

In Marrakesh, the history of the daqqa is inextricably linked with that of Hadj Abdeslam’s family. The young Hadj was initiated by his father, and soon became a member of the group of his quarter, one of the seven high spots of this art in the famous ‘Red City’. He was intimidated because he had play alongside the other ‘chosen’ members who were mostly a hundred years old!

Aspiring daqqa players are often recruited in traditional circles in the heart of the different branches of the craft guilds. Hadj Abdeslam’s uncle who founded the memorable “groupe des quarante” (group of forty players) was a tailor by profession. The art of Hadj Abdeslam and his companions is one of the many facets of the legendary cheerful and welcoming atmosphere to be found in Marrakesh. Custom would have it so and all this combines perfectly with life as it is lived in the great gardens just outside the city.

Jaafar Kansoussi – sociologist

Excerpts from the recitative, aït

With the name of the Bountiful we begin

The name of the Almighty

A prayer on the Beauty of Beauties

Taha and Yassin

We beg Your intercession, O Lord of all Envoys

O our Prophet

O my Happiness, O our Intercessor

May the prayer of Allah be with you O Korashite

O Mohammad most honoured Messenger…

O ye of the zaouia, I come hence as a pilgrim

To find my bronze-eyed gazelle once again…

(Translated from the Arab by Jaafar Kansoussi)

Translated by Délia Morris

- Reference : 321.028

- Ean : 794 881 497 928

- Main artist : La Daqqa (الدقّة)

- Year of recording : 1999

- Year of publishing : 1999

- Music style : Daqqa

- Country : Morocco

- City of recording : Paris

- Main language : Arabe

- Composers : Traditional

- Lyricists : Traditional

- Copyright : Institut du Monde Arabe